Puzzled, I looked up the word in two of our modern dictionaries. Both defined labyrinth as synonymous with 'maze' - complicated, confusing, irregular, and difficult to navigate. But, fascinatingly, the illustrations referred to by such definitions looked similar to this:

Take the time to carefully trace the path from point A to point B. What do you discover? Is it confusing? Irregular? Difficult to navigate? One thing is certain: there are no choices to make - there is only one path, albeit winding. The word for this is unicursal, as opposed to multicursal (more than one possible path).

Take the time to carefully trace the path from point A to point B. What do you discover? Is it confusing? Irregular? Difficult to navigate? One thing is certain: there are no choices to make - there is only one path, albeit winding. The word for this is unicursal, as opposed to multicursal (more than one possible path).

How often do we find a blatant contradiction of definition versus depiction in our dictionaries? Dictionaries, we must remember, reflect our common usage, and, therefore, our expressed understanding - or misunderstanding - of a word. So, where did the misuse begin? Why has it been perpetuated? And perhaps, most importantly, what new insights can we gain from this exploration?

We may not find conclusive evidence today, but we can begin the journey. Are you willing to enter the labyrinth with me in search of the center? I wonder, will we encounter false stops and starts, or will our travels be smooth?

Let's start with our usual method: tracking a word's history. The early English Renaissance appears to be labyrinth's approximate point of entry into our language: referring to the product of Daedalus's machinations, it was borrowed directly from the Latin labyrinthus, itself a slight adaptation of the Greek laburinthos of Homer's account. Rather a straightforward path, don't you think? The center seems tantalizingly close.

However, the trail begins to turn. Although the Greek laburinthos means 'maze,' for some reason, the 15th-century English did not use their preexisting word 'maze' to translate the myth text - instead, they imported this one. Why? We recall that they did choose to employ the Middle English word 'clue' to describe the thread that Theseus held; why, then, did they decide to enrich their language with this foreign one? Did it express a new concept, one they had not yet encountered?

Thankfully, ancient depictions of Daedalus's maze still survive today, and may give us a clue (no pun intended!). In Piadena, Italy, a Roman labyrinth mosaic dating from 25-50 AD depicts Theseus and the Minotaur grappling its center. This labyrinth, however, is not a maze: it is a square network of passages with one path toward the center, and the same path out. In his marvelous pictorial book on this subject, "Labyrinths & Mazes," Jürgen Hohmuth articulates this conundrum: "A contradiction between legend and portrayal becomes particularly obvious with Roman labyrinths: there is only one path in and out. Why then did Theseus need Ariadne's thread?" (p. 64) In Switzerland, a circular mosaic labyrinth crafted around 200 AD portrays a similar theme:

Our question remains: how can a labyrinth with one flowing path be mistaken for a terrifying maze? Is this a psychological phenomenon that we can attribute to the darkness and depth of the Minotaur's prison? Are there any labyrinths free of this maze reference that can rescue us from this subterranean trap?

Our question remains: how can a labyrinth with one flowing path be mistaken for a terrifying maze? Is this a psychological phenomenon that we can attribute to the darkness and depth of the Minotaur's prison? Are there any labyrinths free of this maze reference that can rescue us from this subterranean trap?

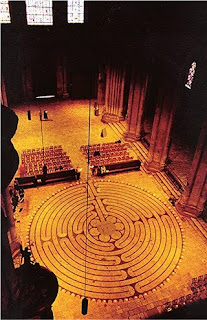

Yes, there are many examples of unicursal labyrinths independent of Daedalus' creation, dating from both before and after the aforementioned Roman mosaics. They have low or no walls, so that the center is always in sight; one entrance that doubles as an exit; the center as goal; and one sinuous path. The earliest examples of the labyrinth pattern date from 1200 BC and arguably even earlier, and labyrinth designs have been unearthed in Europe, Asia, Africa, and North and South America. Throughout this vast history, various peoples have utilized larger versions for religious rites and community rituals. In the Christian era, for example, worshipers have traced church labyrinths in prayer and meditation, often on their knees. Here is an existing example still in use in the famous medieval cathedral in Chartres, France:

So, is labyrinth correctly defined as a winding passage with only one opening, where the goal is the center? Can it be called a labyrinth if it retains these qualities, but is also a maze inside, offering many choices? Or, as the Roman mosaics depict, was it never really a maze at all, but just felt like one because Theseus could not see his way in or out?

So, is labyrinth correctly defined as a winding passage with only one opening, where the goal is the center? Can it be called a labyrinth if it retains these qualities, but is also a maze inside, offering many choices? Or, as the Roman mosaics depict, was it never really a maze at all, but just felt like one because Theseus could not see his way in or out?

Perhaps our human nature reacts similarly in the midst of either a maze or a labyrinth: when we do not reach the center (or the exit) in a direct fashion, we experience frustration, irritation, even panic. Maybe, in the rush of our modern world, we need to slow down and rediscover our sight. Then, we will recognize a labyrinth for what it truly is: not an "über-maze" constructed to defeat us, but a potentially liberating experience disguised as a path of singular constraint. A symbol, some say, of the journey of life.

If enough of us do this, then the next dictionary definition of labyrinth will reflect our discovery.

Glad to walk this winding path with you -